Dreams. Details.

New destinations.

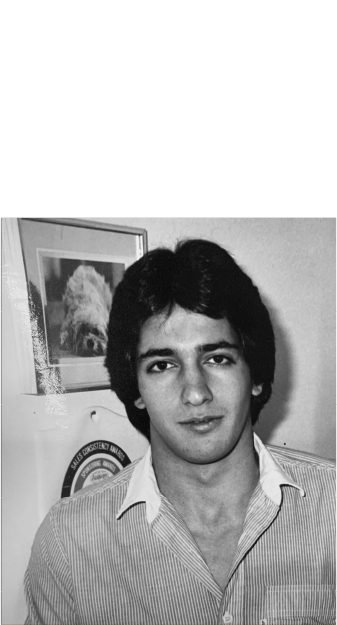

I grew up in the sixties and seventies in Tehran. Modern and sophisticated, there were close to five million people living in the city itself and over eight million in the metropolitan area.

It was a busy, thriving metropolis full of Western influences.

Clothes on the runway in Paris and Milan one week would be on the streets of Tehran by the next.

I was the baby in a family of four; that included my oldest brother Davood, another brother Bijan, and my sister, Zohreh older by four years.

My father was in the military with expertise in finance and accounting and since his salary wasn’t enough to provide for us, he often worked two or three other jobs. My mother took care of the house and us kids. This was considerably different than when they were children. They had nothing, not even sure of the basic necessities of life.

We were never that poor, but had little more than we needed, just food, clothes, shelter and education.

I don’t remember ever even having a toy, but never felt deprived.

My brothers, cousins and I would create our own fun. We were happy, had great friends, a carefree life, and a loving and traditional family.

My father was as concerned about his children’s character as their education and career advancement. He stressed the importance of hard work and respect for others through service. These are values that still guide me today.

I didn’t have much self-awareness as a kid. Quite the opposite. I was self-absorbed and only interested in doing what I wanted to do, when I wanted to do it, and with my boundless energy, I always had to be doing something. I could not sit still.

I was also determined to be the best at everything I did, which I believe was a result of a desire to please my dad. If I was going to build a kite, it would be the best kite. Always a perfectionist, re-writing papers over and over again rather than turn them in with a scratched-out mistake.

My youthful curiosity and exuberance constantly got me into trouble.

(I was the best at this too!) It wasn’t out of disrespect, it’s that I couldn’t help myself from always taking things one step further.

My family still tells the gunpowder story. I loved playing with gunpowder. We learned if you took just a bit, less than the size of a pinky fingernail, and struck it with a stone, it would create a small explosion, sort-of a do-it-yourself firecracker if you will.

One day, near the end of sixth grade, I was playing in the school’s courtyard and dropped the ink jar I stored it in. It shattered on the ground, leaving the gunpowder in a pile of broken glass. Rather than getting upset about the loss, I saw an opportunity, found a loose granite tile, set it atop the spilled pile, and jumped on it with all my might.

The school shook hard, windowpanes broke. It was a miracle that I didn’t get hurt or even killed. I probably should have been expelled but my teachers stepped in to save me. At the top of my classes, my teachers always protected me, and this to me, seemed like one of the first examples of undeserved good fortune that had a positive effect on my attitude about life.

It supported my belief that some elusive luck followed me. But I could never determine if it was pure luck or was it my attitude that created the luck. I do know that

these two symbiotic forces – luck and attitude – are at work in every life, and how they interact ultimately determines destiny.

It was a simple time, and I didn’t think much beyond it. In my mind, my life and future were set. I wanted to be like my big brother Davood, a pilot in the Iranian air force, who I completely idolized. I would graduate from high school and follow in his footsteps.

When I was sixteen, things in Iran started to change. One day, Davood’s plane malfunctioned during a routine training mission and he had to eject only a few thousand feet above the ground. He survived, but it was a harrowing experience. My father was suddenly less enthusiastic about seeing his youngest follow the same path as his oldest.

Less than a year later, our country began going through changes that threatened our entire way of life. In 1978, a new, more radical wave was sweeping through Iran. My father, in his wisdom, saw the storm clouds on the horizon and the forces that would eventually lead to the upheaval of the Islamic Revolution. He resolved to get me safely out of the way.

My brother Bijan had already emigrated to the United States for college with one of my cousins, so at seventeen, my family put me on a plane to join them. Up until then, the only plane I had ever been on was a military C130 – basically a metal tube with no insulation.

My journey to the United States was, and still is, the longest of my life:

Tehran to London, London to JFK, over to LaGuardia, LaGuardia to Chicago O’Hare, O’Hare to Denver, and finally, to Colorado Springs. After two days, five planes, and six airports, I arrived in a remote Rocky Mountain town named Colorado Springs.

I was in shock when Bijan picked me up at the airport. My reference for the US came from movies, television and magazines. I expected Manhattan or Hollywood, but suddenly found myself in a town of about 250,000 and people wearing clothes that had gone out of fashion in Tehran at least a decade earlier.

In Iran I had been an excellent student, and contrary to common belief, Iranian schools at the time were actually more advanced than American public schools. I could have gone straight to college-level work, but I knew I needed to know more than academics to succeed. I was in a whole new world, so I registered as a senior at Coronado High School and jumped into the world of American teens.

Looking back, that was one of the best decisions of my life. At Coronado High I wasn’t challenged by my classwork. My real course of study was the American way of life. And my fellow students were excellent teachers.

I observed was how relaxed my classmates seemed to be about schoolwork and how much focus they put on having fun. This was the opposite of the way things had been back home. At that time in Iran, there was one national test that everyone had to take and it determined your entire future. It was much more important than the SAT is to American students today. Seniors in Iranian high schools spent the entire year preparing for that test. Students often stayed home to study when their parents went on vacation. I still remember seeing kids outside on the street on warm nights, reading their textbooks under streetlamps while the rest of the family slept.

In my new home, students also studied and thought about college. But they also seemed to believe that having fun was a big part of being a high school senior.

That view of fun – that it was a fundamental right – was the most ‘foreign’ idea I had ever encountered.

I dove right in.

In America, there were fewer rules, and a more relaxed attitude following them. Sometimes people even scored points for breaking the rules, as long as they weren’t being destructive. I soaked this up and reveled in a new creativity, imagination, and independence.

American teens also seemed to have a different view on authority. In Iran, we were taught to have an almost unshakeable respect, beginning with our parents. It would have been unthinkable to ever speak back to or disagree with a parent or teacher. Everyone knew his or her place and the expectations place up on them. This created a high degree of order, but also encouraged rigidity. It made it difficult to be an independent thinker.

This now provided me with two approaches to life; one traditional and one modern.

The question “Which one was better?” went constantly through my mind.

One day, with little fanfare, I simply realized one didn’t have to choose. One could have both. Instead of limiting my options, my world actually grew. I had options.

There was no need to reject the old in order to accept the new. I could keep the values and lessons I knew were important while embracing the new freedom and endless possibilities found in the United States.

Life showed me a new door in a new country, a place I never expected to be. I opened it and walked through with my typical enthusiasm. Excited about my new insight, I realized there might be many other doors.

Instead of asking which approach is better, the question became: how many approaches are out there?

Along with the desire to draw from all of them until I found the answers that worked for me. This simple understanding revolutionized my life.